Systematic Investing

A System-driven Approach to Investing and Building Wealth

It's Time to Capture the Potential of Stocks Leveraging Quantitative Techniques

Like Hedge Funds Do ...

Our Quantitative System Develops Model Portfolios

With a Strong Track Record of Returns

Far Outpacing Benchmarks

The Editor's Desk

Dear Fellow Investor,

You have arrived at this page today in your search to discover a better way to invest and capture the potential that the stock market offers. A way that is more efficient, powerful, and consistent. Fortunes have been made through disciplined investing, and there's no reason why we can't do that as well. My name is Tarun Chandra and let me explain more about quantitative investing, our system, and its track record. That's the only way to empower you to decide if this system can get you closer to achieving your desired investing goals by setting you on a path of building investment wealth over time. On this page, we begin with the journey into systematic investing, and additional pages provide insights into the track record and the potential of small cap stocks.

Sincerely,

Tarun Chandra

Graycell Advisors

Quantitative Model Investing

A system-driven unemotional approach

embraced by some of the best hedge funds

"If you do fundamental trading, one morning you come in and feel like a genius, your positions are all your way… then the next day they’ve gone against you and you feel like an idiot… so in 1988 I decided it’s going to be 100% models, and it has been ever since... and it turned out to be a great business."

Jim Simons

Mathematician, Founder of Renaissance Technologies hedge fund

Jim Simons is a legendary hedge fund manager, and his Renaissance Technologies hedge fund has one of the best, if not the best, performance track records on Wall Street even while charging the highest fees - over 40% of profits. His fortune is estimated by Forbes to be above $15 billion. Renaissance is a 100% quantitative-driven shop, which means it uses systematic investing incorporating rules-based algorithms and models to achieve returns. Unfortunately, they don't accept money from individuals. In fact, in its top-performing Medallion Fund, the firm returned all the outside money in 2005 and only invests the money of in-house employees. Let us understand why systematic model-driven investing has become such a powerful strategy that continues to drive multi-billion dollar active management funds, like those of Ray Dalio's Bridgewater Associates, the largest hedge fund, and Steve Cohen's Point 72, to shift towards quantitative model investing.

One of my academic areas of specialization was Systems Analysis and Design. It takes time to design a system since there can be many possibilities to consider and address based on the function. But once a system has been developed it usually performs consistently based on the parameters or rules that have been assigned, with some optimization over time to adapt to evolving market conditions. A great deal of analysis and experience goes into designing a system and testing it under various situations, which then builds sufficient confidence and trust in the system. The discipline to follow the system diligently is a prerequisite to achieving the objectives for which the system was designed in the first place. Most failures occur due to a lack of discipline. Extensive research has been conducted on the efficacy of systematic decision-making compared to expert or discretionary decision-making. Empirical evidence has come out consistently in favor of model-driven decision-making, and this is relevant for investing as well.

Paul Meehl, an American psychologist who is considered the founding father of the science of the predictive importance of quantitative models over human judgment, studied the outcomes of predictions in many different settings. He discovered a preponderance of the evidence that predictions based on mechanical [algorithmic, quantitative] methods of data combination outperformed clinical [subjective, informal, in-the-head] methods based on expert judgment. Decades ago in his seminal work, Clinical Versus Statistical Prediction: A Theoretical Analysis and a Review of the Evidence, Meehl noted the efficacy of the quantitative models, saying:

"There is no controversy in social science that shows such a large body of qualitatively diverse studies coming out so uniformly in the same direction as this one … predicting everything from outcomes of football games to diagnosis of liver disease."

Paul Meehl

Psychologist

In a 2000 paper by William Grove, et al, titled ‘Clinical versus Mechanical Predictions,’ the authors noted,

Superiority for mechanical-prediction techniques was consistent [over humans/experts], regardless of the judgment task, type of judges [experts], judges' amounts of experience, or the types of data being combined.”

Grove, William; Zald, David; Lebow, Boyd; et al

Psychological Assessment, Mar 2000

Why does systematic decision-making using even uncomplicated quantitative models performs better than expert opinions?

The answer lies within us. It is the behavioral tendencies embedded in our thinking that handicap our decisions.

Research reveals the human mind is very capable of consistently misjudging the world.

We are prone to over-or-under-estimating, being overconfident in our analysis while doubting data contrary to our opinions, and using perceptions to create or fill up what doesn't exist. It's easier to operate that way.

Psychologically, our opinions are filtered through our natural biases. Such filtration is not always bad when it comes to everyday mundane decisions or situations of survival when the elaborate time-consuming analysis is counter-productive. But these biases create a difficult situation in decisions which involve money and emotion.

"All these psychological tendencies work largely or entirely on a subconscious level, which makes them very insidious...Wherever you turn, consistency and commitment tendency [and cognitive biases] are affecting you."

Charlie Munger

Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, Warren Buffett's investment partner

Charlie Munger, Vice-Chairman of Berkshire Hathway and long-term investment partner of Warren Buffett, refers to this cauldron of emotions, biases, and tendencies acting in concert to push us towards an irrational action as the "Lollapalooza effect." In his book, Poor Charlie's Almanack, Munger notes several cognitive biases we should be aware of to make better decisions.

We may have already witnessed these irrational tendencies in our investments.

Most of the time the “gut-feel” investing decisions eventually leave one poorer and feeling exhausted, disappointed, stressed, and frustrated.

I know these feelings as I have experienced them too.

Computer algorithms simply don't feel that way.

A legitimate question is why experts perform poorly even when they’re given the model’s output before making their decisions.

Once again it’s our propensity to overestimate our abilities, and the feeling that we possess special insight that can allow us to enhance the model’s decision.

So the experts when given the same model's output end up modifying it and making the results poorer. Something as mundane as a rough commute or a missed train can affect the way we perceive things. Furthermore, the decision-making can be inconsistent from person-to-person even when they look at the same data. All these factors significantly diminish our ability to bring the perceived “enhanced” performance compared to that of a system's emotionless and model-driven decision-making.

"Unrealistic optimism is a pervasive feature of human life; it characterizes most people in most social categories. When they overestimate their personal immunity from harm, people may fail to take sensible preventive steps."

Richard Thaler

Nobel Prize Winner, Behavioral Economist, and Author

In October 2017, Richard Thaler, a behavioral economist from the University of Chicago, won the Nobel Prize for his work exploring the biases that affect how people absorb information and arrive at decisions. In other words, how people are not rational as is often assumed in econometric models, but instead have mental quirks or biases, limited self-control and rationality, and social preferences that lead them towards irrational behavior and shape market outcomes.

Thaler is not the first person to receive the coveted Nobel Prize for work in the field of behavioral impact on decision-making. Other Nobel Prize winners who have contributed to this field include psychologist Daniel Kahneman and economist Vernon Smith, who both won the Nobel in Economic Sciences in 2002, and economist Robert Shiller, who won in 2013. Daniel Kahneman, who was inspired by Meehl’s work, drew on the decades of research in psychology in his famous book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, and noted the following:

"Several studies have shown that human decision makers are inferior to a prediction formula even when they are given the score suggested by the formula! They feel that they can overrule the formula [model] because they have additional information about the case, but they are wrong more often than not."

Daniel Kahneman

Nobel Prize Winner and author of book Thinking, Fast and Slow

What the studies and empirical evidence above tell us is something probably you have already observed or experienced.

How many times have you encountered analysts and economists making wrong calls?

It happens all the time.

If these professionals who have access to all kinds of data, analysis tools, and support teams continue to be frequently wrong in their predictions, then it’s a fairly tall order to expect an individual investor to be consistently right in making judgment calls. We used to often say on Wall Street that economists are usually right when they offer a forecast but no time frame, and never right when they offer both.

The bottom line is that if you’re going to invest using system-driven, quantitative models, just don’t keep enhancing the model's output with your judgment calls. You may be thinking of pushing the performance ceiling higher, but studies strongly suggest that the performance ceiling is being lowered.

Trust Jim Simons to know something about quantitative model investing when he noted,

"...if you’re going to trade using models, just slavishly use the models. You do whatever the hell it says no matter how you feel about it in the moment."

Jim Simons

Mathematician, Founder of Renaissance Technologies hedge fund

My Journey to Quantitative Modeling ...

I started working on Wall Street in the early nineties as an Analyst.

I first worked as a Buyside Analyst (for an asset management firm) and then as a Sellside Analyst (for brokerage and investment banks). The research coverage comprised various sectors, including Software, Telcos, Semiconductors, IT Services, Medical Devices, Pharmaceuticals, etc. The focus was on the US small cap and midcap stocks.

Things were going well when the first blow-up happened. A software company missed its numbers. Out of the blue, Microsoft incorporated some of this company’s key product features into their next release of Windows, and this company was busted. A hard lesson learned.

There is a saying in Wall Street research departments that if you haven’t had an earnings miss yet, then you haven’t been an Analyst long enough. At Goldman Sachs, a helmet used to be passed around in the research department to the analysts who suffered a stock blow-up. The idea was to hit the helmet with a hammer every time a blow-up occurred. Needless to say, this helmet was seriously battered.

Over time, I got better at picking stocks but also had my stumbles. Some of them were unavoidable. But there were others where I hung on to an opinion too long, looked at things differently, or reposed too much faith in management guidance, etc. And I was not alone in these stumbles. Research departments at most Wall Street firms have similar stories. Analysts and strategists who have scaled greater heights were also riding the same cycles of success and failure.

Consistency was elusive.

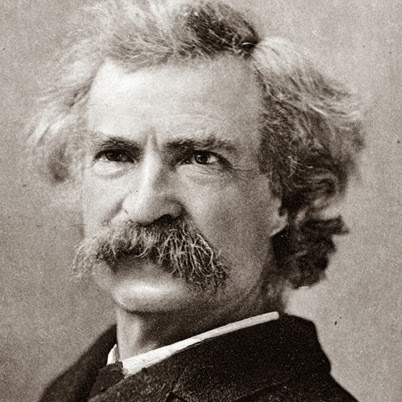

It ain't what you don't know that gets you into trouble. It's what you know for sure that just ain't so.

Mark Twain

American writer and humorist (attributed but unverified quote)

As I saw it, consistency was sought hard, but hardly achieved.

Even the best succumbed to the human reversion to mean or average performance over time.

Remember Elaine Garzarelli making a 1987 prescient call for an impending market crash, Goldman Sachs market strategist Abby Joseph Cohen from the nineties calling the bull market, Meredith Whitney from Oppenheimer in the late 2000s calling for a Citigroup dividend cut, which happened, and then a municipal bonds sector debacle, which never did. All of them had their flashes of brilliance, but could not maintain consistency over a prolonged period. The list of people goes on from market strategists to economists to analysts to portfolio managers. No wonder it is so difficult to beat the market indexes and why most active portfolio managers underperform the benchmarks.

Even if you haven’t heard of experts getting it wrong, you can simply check out a company that missed earnings today or the daily list of stocks that declined sharply. You’ll discover that after the stock has cratered, there are now many revisions of price and rating. A majority of times, the ‘Sell’ rating is forced on to the experts, and is forced upon post-event. Heck, anyone can do that.

Even after a few quarters or a year, even if our conviction is finally proven right, do we individual investors possess the resources to weather a substantial decline? Even institutions with deep pockets can find it hard.

How many such deep portfolio drawdowns can one weather?

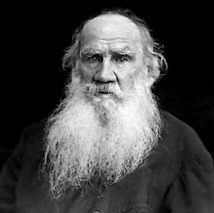

The most difficult subjects can be explained to the most slow-witted man if he has not formed any idea of them already; but the simplest thing cannot be made clear to the most intelligent man if he is firmly persuaded that he knows already, without a shadow of doubt, what is laid before him.

Leo Tolstoy

Russian writer regarded as one of the greatest of all time

I left Wall Street, bitten by the entrepreneurial bug, and joined one of our investment banking clients.

But the love for Wall Street never left me. I continued to search for ways to create greater predictability in my research; diminish the unexpected; read signs of trouble a little better; to survive an earnings season.

Very early on, I developed a penchant for analyzing market data using various tools to create models that assist in building a funnel for ideas. That was the Systems Analyst side of me. I developed models with Professors as a graduate assistant, modeling econometric series with the idea of predicting short-term interest rates and the timing, direction, and size of the next move by the Federal Reserve. I brought that mindset to my Wall Street job as well. I was looking for certain tendencies for stocks that perform well, for recognizing patterns can breed consistency. At the same time, I was also growing confidence in my various systems. I did not wish to rely much on human interaction to determine investment outcomes.

Once I winded out of the Wall Street and Main Street roles, I decided to continue developing model portfolios that can outperform benchmark indexes consistently. I found the results of these quantitative portfolios would consistently and materially outperform the benchmarks. I started offering subscribers these model portfolios. That’s what I have been doing since - using quantitative analysis to develop model portfolios to outperform benchmarks and manage risk. The risk cannot be eliminated, and in some segments like biotechs and small caps, it will always remain elevated. But the risk can be diminished so that the portfolio can benefit from the many more promising opportunities these segments offer.

As an analyst and investor I’ve made mistakes like the ones cited here, and learned from them.

Through the years, one thing has become clearer.

Consistently outperforming the market on an annual basis is hard to achieve for individual investors without the discipline of rules-based systematic investing.

Many investors are smart, but still not consistently successful. There are rare smart folks who achieve consistent performance. As individual investors, we do not have ready access to exceptional money managers focused on managing multi-billion-dollar portfolios of institutional and high net worth money.

Success in investing doesn’t correlate to IQ. Once you’ve ordinary intelligence, what you need is the temperament to control the urges that get other people into trouble in investing.

Warren Buffett

Legendary Investor

Consistent returns require discipline and rules-based investing unclouded by impulsive judgments.

Many individual investors desire and aim for doubles and triples when they invest, and in the process are willing to assume significantly more risk. The doubles do come occasionally. But more often than not, an investor will find such gains being offset by other positions that are either closed for significant losses or continue to be held year-after-year in the hopes of a rebound.

Model-driven investing guides us to capture whatever returns the market can reasonably offer and then outperform that level.

This rules-based systematic investing helps us get to the next base, and then to the one after, keeping us moving forward. And that’s how the portfolio returns accumulate over time. Even if the home runs don’t happen, an investor still wants to collect a solid portfolio return outperforming the benchmarks and then keep building on it in the years ahead. Focus on the portfolio returns and not individual stock returns. A seasoned investor is aware of the market's ability to often surprise negatively.

Think of the investment portfolio as a bus to move us forward to the next stop, or sometimes even further.

But be prepared to get off if the situation warrants it. There will be another bus, or the next idea, coming soon to continue our journey forward. When I started as an Analyst and used to show annoyance at missing an idea, the Director of Research used to tell me:

Stock ideas are like the New York subway. There is one every few minutes.

Director of Research

A New York investment bank

The message the Wall Street veteran was trying to communicate was that opportunities are plentiful and never cease.

Emotionless investing is a critical prerequisite for successful investment outcomes. Model-driven investing provides the discipline to invest without emotions. Just like hedge funds benefit from their quantitative investing strategies, I believe we can also grow our investment portfolio leveraging the discipline of systematic model investing and enhancing the probability of achieving consistently superior returns over benchmarks.

I have provided empirical evidence from studies to support the argument for quantitative model investing. Feel free to do your research. We must not ignore the consistent success of funds pursuing model-driven investing run by stalwarts like Jim Simons and Ray Dalio.

Investors risk diminishing the potential of their investment portfolios by ignoring systematic investing strategies.

How Systematic Investing Works?

The model portfolios use quantitative models to guide stock selection.

The algorithms, which are instructions or rules in a quantitative model, are used to create the monthly model portfolios. Each month the investment model analyzes the stocks and offers ideas relevant to the strategy (biotechs, healthcare, small caps, etc.). Towards the beginning of each month, the portfolio gets adjusted as needed. Weaker stocks are closed and replaced with stronger ones from the list. By performing such a rotation when necessary, the investment model positions the portfolio to hold a promising group of stocks - those the system determines to have a stronger potential of delivering benchmark-beating returns.

Based on the focus of the model portfolio, there may be exposure to a single industry group, like biotechs, or a single sector, like healthcare, which can create more concentrated risk and volatility as opposed to a more diversified portfolio across sectors. Broader indexes, like the S&P 500, are heavily diversified across industry groups. The model portfolios also have a limit on the total number of positions, like 8 or 10, which can create higher volatility when compared to benchmarks holding hundreds of stocks. However, the concentration in the model portfolio has a meaningful benefit - stocks that perform well can have a larger impact on the portfolio performance than the same stocks in a broadly diversified portfolio. It also means that declining stocks in the model portfolio can have a larger impact as well, when compared to an index.

As will be observed from the results, the model portfolios have materially outperformed over longer (2+ years), medium (1 to 2 years), and shorter (1 year) duration most of the time. The methodology has allowed Graycell model portfolios to historically deliver market-beating performance, though past results are not indicative of future performance.

What The Systematic Investing Service Is Not...

Let us be clear about what the model-driven systematic investing service is not. It is not a guaranteed, get-rich-quick scheme or an investing panacea.

Our systematic investing approach is deliberate and long-term. One must have at least a 2-3 year time horizon to benefit from this approach.

Investors cannot avoid individual stock losses since they are an unavoidable part of investing. But losses can be tried to be managed with a portfolio approach. As investors, we must recognize that the most important thing is to have reasonable and realistic expectations from the stock market, which is a risk-reward market and not a risk-free market. There is a 10% annual return expectation over the long term from the stock market. There are years when the market climbs 20% or higher, particularly after a bear market, but such years are less frequent. In addition, bear markets or corrections can take away 10% to 30%, and sometimes more, from an index.

Keeping all this in perspective, our objective is to outperform benchmarks meaningfully and aim to be consistent.

It is how a portfolio grows over the years and creates investment wealth.

The Market is About Results, Not Just Hope

Many investors get caught up in hope investing.

Quantitatively-driven model portfolios do not rely on hope.

They deal with the data as it exists. There is no hoping or swearing.

You hold the positions or fold them just as the data guides.

That is what prudent investing requires. A controlled emotional state of decision-making. Minds feed on emotions. Over the long run, emotions and biases can disrupt investment performance. Recall the underperformance of experts who could not outperform systems even after possessing the same data and the recommended output of the systems.

Emotions and biases are the variables that are always present in experts as well but absent in a system.

It is very hard to take losses. But the performance history bears out that the methodology works. Operating within a rules-based system increases the probability of avoiding deep and total losses and enhancing returns over time.

The focus must be on portfolio returns and not on individual stock returns.

It is great to be a person of conviction. But stubbornly sticking to your guns may have a real downside for investing, as markets can be irrational.

You may be right in the end.

But will you be there in the end?

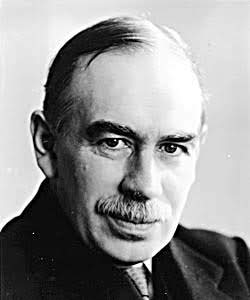

As noted British economist and an active investor, John Maynard Keynes so very pragmatically noted,

The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

John Maynard Keynes

Economist

Graycell Advisors, and its affiliates, officers, employees, families, and all other related parties, collectively referred to as ‘Graycell’ and/or ‘we,’ is a publisher of financial information, such as the Prudent Small Cap, Prudent Biotech, and Prudent Healthcare newsletters. We are not a Registered Investment Advisor (RIA). Historical performance figures provided are hypothetical, unaudited, and based on our proprietary analysis and system performance, back-tested over an extended period. Hypothetical or simulated performance results have limitations, and unlike an actual performance record, simulated results do not represent actual trading and consequently do not involve the financial risk of actual trading. The performance results obtained are intended for illustrative purposes only. No representation is being made that any account will or is likely to achieve profit or losses similar to those shown. Past performance is not indicative of future results, which may vary. All stock and related investments have a degree of risk, which can result in a significant or total loss. In addition, the biotech industry and small caps are characterized by much higher risk and volatility than the general stock market. Information contained herein is general and does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual investors. If you decide to invest in any of the stocks of the companies mentioned in the newsletters, samples, alerts, etc., sent to you or available on our websites, you can and may lose some or all of your investment. You alone are responsible for your investment decisions. Use of the information herein is at one's own risk. We are simply sharing the results of our model. Nothing should be construed as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any securities, and we are not liable nor do we assume any liability or responsibility for losses incurred as a result of any information provided or not provided or not made available on time, herein or on our website or using any other medium. We cannot guarantee the accuracy and completeness of any information furnished by us. We may or may not have existing positions in the stocks mentioned in our reports. Our models are proprietary and/or can be licensed and can be changed or revised based on our discretion at any time without any notification. Subscribers and investors should always conduct their due diligence with any potential investment and consider obtaining professional advice before making an investment decision.

© Graycell Advisors. All rights reserved. Any act of copying, reproducing, or distributing this newsletter whether wholly or in part, for any purpose without the written permission of Graycell Advisors is strictly prohibited and shall be deemed to be copyright infringement.

© 2003-2024 Graycell Advisors. All Rights Reserved. USA